What Does "Truth" Mean Now?

The Neo Axial Age, Part 8

"Concerning my own humble person, I frankly confess that as an author I am a king without a country and also, in fear and much trembling, an author without any claims." — Søren Kierkegaard

The world has changed. We all feel it.

It is changing still, faster every day. And whether you’re glad for these seismic shifts in the ground of our common life, or full of dread because of them, or somewhere in between, one fact remains true for all of us:

We are struggling, and struggling mightily, to keep up.

The great thinker and therapist James Hollis has written that “the soul has a demand for meaning, a longing for something larger in life. Each of us needs to feel the resonance of the soul, that we are participants in a divinely generated story.”

We certainly have no shortage of stories being offered up to explain what’s happening to us in these days. But most are shallow and desperate and shifting too fast in their fevered battle for cultural dominance. Few of the new stories on offer today have roots or substance; they are merely flash and spectacle, feeding on fear or the titillations of rumor and conspiracy. We’ve all but lost the thread of the divine.

I mentioned in an earlier entry how we humans are narrative by nature, how we construct these elaborate stories to live inside — collective dramas of our own making, to help us make sense of the world. We call them worldviews, or cultures, or belief systems, or truth. We enlist millions of other humans to join us inside them. We buy into them so completely we forget they are stories at all. We create our own personal version of The Matrix, then hide our true hearts away within it, willingly exchanging our freedom for the promise of safety they provide.

We use The Matrix as a defense against the terror of the Great Unknown — the terrible fact that we don't really know what we are or what life is really all about, and we don't know how we can know. Confronting this Great Unknown head on threatens to drive us to madness, or at least to despair, so we tuck our hearts away into smaller, more manageable narratives to distract us from our fear.

This strategy has never been perfect. We all still feel unsafe and afraid—very often—and loss always finds its way into our lives, unfazed by our attempts to deny it. But our chosen Matrix does, for the most part, keep the Great Unknown at bay.

At least, it used to, until this most recent century, when the pace of change drastically increased. More has changed in the last hundred years than in the twenty centuries before it combined. As the pace of change races faster and faster year after year, the foundational stories we have always depended on to veil our eyes from the Great Unknown have frayed at the edges and ripped at the seams. The truths our stories assert have been exposed as lacking. The ways they tell us to live no longer make sense.

The world is changing too fast for our stories to keep up.

As a result, the Great Unknown has begun spilling in through the gaps. Questions of meaning, of what truth is, of what it means to be human, of where all this is headed, and whether it even means anything in the end, have seeped uninvited into our public consciousness. Unsurprisingly, this has sparked waves of both terror and despair in many, and provoked an increasing number of alarmist declarations of the coming of the end of the world — which is, of course, the failsafe “panic button” included in nearly all of the cultural narratives we know.

The great Christian theologian and mystic John O’Donohue once said that the two closest companions that accompany every person through life are Death and the Unknown.1 From the moment we are born, Death and the Unknown are right there with us. We are always just one breath away from death, just one heartbeat away from the veil that leads out of this world. And even while we remain here, not one of us knows what's going to happen from one moment to the next. Thus, the unknown is always with us, always just one second away. We are accompanied through every moment of our lives by these two teachers — and they are meant to be teachers, I think. Sadly, though, for most of our lives, most of us do everything we can to convince ourselves they aren't really there.

But Death and the Unknown — they are really there. The enchanting mystery of what it means to be alive, and the strange, pervasive sense of loss that accompanies that aliveness; these are always with us. At the moment, our experience of this loss is too visceral to pretend away, and our fear of what lies beyond the unknown precipice of our future is too foreboding to ignore. The loss and uncertainty of our times have grown too weighty for our current narratives to bear. They can no longer carry them, or show us how to navigate them. The story of our “reality” as we have known it is crumbling under the burden.

What has resulted is a great eruption of fear and anger in our cultures directed toward a great many things: Political division, racism, mass shootings, immigrants and refugees, economic disparity between the rich and poor, the automation of society, the threat of AI, climate change, the many imminent threats to the environment.

All of these challenges matter. They matter a very great deal. But at the root of them lies three existential questions that haunt us to our core. It is these fundamental questions we instinctively do everything we can to ignore, or deflect, or explain away with the bumper-sticker axioms we learned as children, or proclaim away with the comforting stories promoted by our chosen tribe. It is the same questions our ancestors pondered as they sat around their meager fires, lit as a bulwark against the impartial dark, and looked up in wonder at the canopy of stars:

Who are we? Why are we here? What is this really all about?

Who are we? Why are we here? What is this really all about?

WE NEED A BIGGER STORY

We’re great story crafters, us humans. From the beginning of our journey as a people, we have crafted stories — magnificent, wise, prescient tales — to explain the universe to ourselves, to tell us who we are, why we’re here in this marvelous mystery we call life, and what our purpose is in the grand scheme, what we’re for.

Our stories have always given us the essential grounding and scaffolding we needed to make sense of a universe that would otherwise be so baffling and impenetrable as to be absurd, and to make of us an absurdity.

The ancient stories of our race — our great myths, our great religions — have kept us alive. They have pulled us back from the brink of both madness and nihilism. They have given us a framework for understanding who we are, what our purpose is, and what’s really going on in this wildness we call the universe.

At the moment, our great stories are at war. It has been this way for centuries, actually, but as the pace of change has sped up, the intensity of these conflicts has likewise increased. Probably, the story war we’re most familiar with in the West is the one between Faith and Science, which famously began with the Catholic Church’s censorship and imprisonment of Galileo for proving that the earth revolved around the sun. But there is also the story war between Collectivism and Individualism, the battle over whether truth and meaning is primarily to be found in the community or in the individual. More recently, new battlefronts have emerged to create a four-way conflict among all of these competing narratives. So now we have individualists who boldly trust their own uneducated observations over the rigors of scientific consensus, collectivists who renounce all the wisdom of faith traditions in favor of a new paganism that remixes the sacred like memorabilia in a scrapbook, and a large swath of “nones” who reject pretty much all of it as they hold out for a better story.

I think the “nones” have the right of it. They recognize, as I suspect we all do deep down, that none of our current stories can explain the reality we now inhabit, or carry us where we need to go from here.

“Well,” some might say, “why not just toss all the stories and be done with it? Who needs a story, anyway? They’re all just fables, aren’t they?” Certainly, some today are trying this approach. But we’re finding, not surprisingly, that with the loss of story comes the loss of meaning, and meaning is something that we humans cannot live without.

In her book, Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World, Tara Isabella Burton argues that even those who most adamantly reject the idea of needing an overarching religious narrative to guide their lives nevertheless seek out forms of ritual and transcendent experience that curiously mirror the meaning-making stories of their ancestors, albeit in a “remixed” way.

“The Remixed hunger for the same things human beings have always longed for: a sense of meaning in the world and personal purpose within that meaning, a community to share that experience with, and rituals to bring the power of that experience into achievable, everyday life. But they’re doing it differently.” — Tara Isabella Burton

The problem isn’t that we create for ourselves stories to live in. On the contrary, I would argue that such stories are essential for our survival and our thriving. As I mentioned earlier, we humans are narrative by nature. Storycrafting is the primary way we make sense of the world, and even of ourselves. Without a story overlayed atop the quantum fabric of our lives, the whole experience of life devolves into a chaotic jumble of random possibilities and unconnected events.

The problem, rather, is that our current stories have become too small to hold the complexity of the universe as we now understand it. Our current narratives are too limiting, too rigid, and too quickly turn violent when threatened by other, competing narratives. What we need is not no story, but a bigger story, one that is large enough to see all the others, and even to see itself for what it is — namely, an attempt at comprehending what might well be beyond our comprehension. A generous story, if you will, that is able to shift and change and expand as our understanding grows, and is able to treat all of its own limitations with tenderness, and to offer that same tenderness to the limitations of other stories too.

We also need, as much as possible, for this new story to be hopeful, and, as much as possible, for this new story to be true.

A LARGER, MORE GENERATIVE FRAMEWORK FOR TRUTH

There’s an ancient story about a group of blind men who encounter an elephant in the wilderness and start arguing about what it is. One of them touches its nose and declares, “It is a snake!” Another runs his hand across the elephant’s broad side and says, “It is a wall!” The third grabs hold of its leg and proclaims, “It is a tree!” In some versions of the story, the blind men come to blows, because they are each so convinced of their own rightness.

But of course none of them are right. Or rather, none of them are right entirely. For it can be said that an elephant’s trunk is like a snake, and an elephant’s side is like a wall, and an elephant’s leg is like a tree. But an elephant is much more than any of these things. If the blind men had been humble enough to listen to one another, they still might not have guessed what the elephant actually was, but they certainly would have had a much better chance of getting closer to the truth.

I believe this is a prescient story for where we are in Western Culture at this pivotal moment in history.

To my mind, the battle between faith and science and collectivism and individualism really comes down to the fact that there is more than one way of knowing in the world — which is to say, there is more than one path we humans trust in our quest to know what is real and true, more than one means by which we believe we can come to know what we would call “truth.”

In fact, I would say that there are three.

There is the path of Intellectual Truth, certainly. We might include in this category all the scientific disciplines: Astronomy, Physics, Chemistry, Geology, Biology, and so on. These are the truths we know by means of the scientific method, or as close to that method as we can reasonably get.

But there is also the path of Relational Truth. Love, for example, is a force we all know to be real, perhaps the most real thing of all, yet it is not something the scientific disciplines can easily capture or quantify. It is a relational reality, and it is relationally perceived. Yet is it as real and as true as any scientifically measured object, like say Mars or the quantum field. Other aspects of relational knowledge that may fall in this category include the social sciences, psychology, the arts, the study of relationship intelligence, and even the study of human history, as it is fundamentally relational.

The third path is what I would call Contemplative Truth. In this category we might include all of the spiritual and intuitive disciplines of prayer, meditation, contemplation, religious mysticism, sacred writing and art, as well as the devotional study of sacred texts. The prophetic arts would also fall under this category, but only so far as they are rooted in the more grounded disciplines of true contemplation.

Historically, we have tended to pit these ways of knowing against one another. Each way of knowing has presumptuously claimed exclusive access to all meaningful truth, rejecting any insight from the other paths as illegitimate. The masses have been rallied to choose sides in these conflicts. So we have. We have endless debates, all of them leading nowhere. We judge the people in the other camps as fools and idiots. We start thinking the world would be better off without “those people” mucking up the works…which is, of course, the first step toward our own self destruction, though we rarely see it as such.

Yet, isn’t it just possible that we’re just a bunch of prideful blind men arguing over an elephant?

A MORE WHOLISTIC APPROACH TO PHILOSOPHY

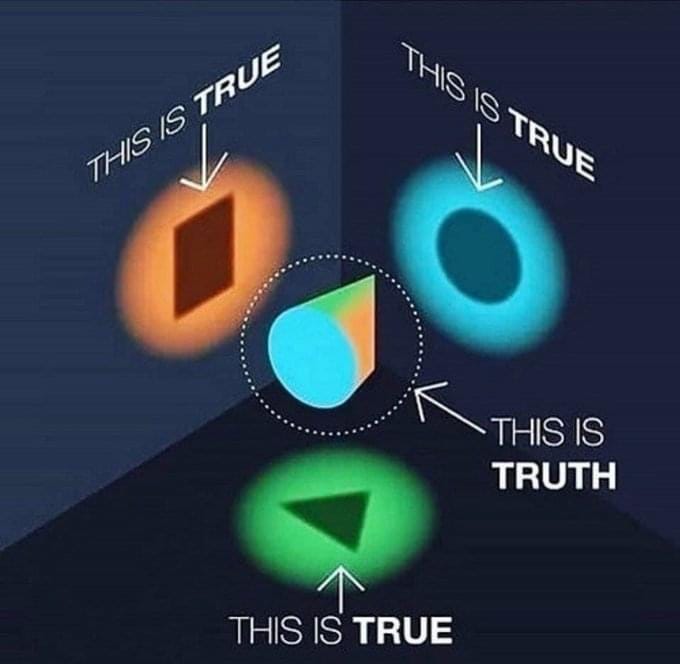

I love this graphic.2 I think it sums up our current situation well. Truth, by which I mean, the actual answer to our three core questions — Who are we? Why are we here? What is this really all about? — is opaque. The answers we seek are not obvious. They are not easy to find. Try as we might, we can’t seem to uncover them through direct observation. We have to come at them from the side, feel them out from the edges, like trying to make out someone’s face through the corner of your eye.

I believe I can trust scientific knowledge, insofar as I always keep in mind that it is a work in progress, and many of its “facts” have later proven to be false, or completely misunderstood. Through scientific inquiry, we have grown immensely in our understanding of the universe we inhabit. Yet it is still, more often than we like to admit, a method for feeling our way in the dark.

I also believe I can trust the longstanding truths revealed through contemplative wisdom, insofar as I always keep in mind that our understanding of spiritual truth is perpetually nascent, never extending beyond the level of a toddler, on account of our limited lives and the limitations of our perspective, living as we do on this tiny rock in the corner of this vast and incomprehensible universe.

Likewise, I believe I can trust in the grounding insights revealed through relational intelligence, my intimate connection to everything and everyone, and their intimate connection to everything else. Yet even here, I must be mindful that my relational perceptions are often warped by my own shadow play, and relationships themselves are always in flow, ever changing and shifting, so that what was true sixty years ago or sixty seconds ago might not be true now.

All three of these are admittedly muddled ways of knowing, but for all their flaws, they are trustworthy enough to reveal something of the actual answer to our three core questions:

Who are we? Why are we here? What is this really all about?

Besides, like the blind men’s hands on the elephant, they are, for the present, all that we have.

I was encouraged to discover that there are versions of the story of the blind men and the elephant where the blind men don’t fight at all. Rather, they share their findings with one another and conclude that there must be a greater mystery at play than any of them can discern.

The time has come for us to stop pitting these ways of knowing against one another, and instead, recognize them for what I believe they actually are: complementary streams of insight that are all speaking in their own way about one ultimate Reality.

As the graphic so beautiful illustrates, I don’t believe the three ways of knowing are actually in conflict at all, but are meant to act in concert, so that the more we know of any one of them points to revelation in the other two. It's a bit like peeking in at the same truth through three different key holes in three different doors. What we see may initially seem vastly different depending on which keyhole we use. But ultimately, I believe we will come to realize that all three key holes are peering in at the Same Thing, and that each line of understanding will inevitably complement and align with the other two.

Under this larger and more collaborative framework, the three ways of knowing function as three senses, something akin to sight, hearing, and touch, and the revelations of each sense is informed by and respectful of the other two, so that through a merging of their combined insights over time a more complete understanding of “the truth” is revealed. In essence, the deep intelligences of spirit and relationship and scientific inquiry would thrive in generative conversation rather than struggle in perpetual conflict with one another. They would act as allies to one another rather than enemies in our shared longing to uncover the truth of who we are, why we are here, and what the universe is really all about.

It is, admittedly, an imperfect solution, because we are imperfect, and all too prone to turning our stories into sacred cages and locking ourselves inside them to hide our eyes from the Great Unknown. In such a journey of unfolding revelation as we must undertake from here (and, indeed, have already undertaken), we must use story crafting as a tool, but never as a final destination. We must hold our stories loosely. We must test them, refine them, and change them as new revelations come into view. The point is not to get it all right completely and without error. How could such a thing ever be possible with fallible beings like us? The point is to craft a story that allows us to seek the truth with all our hearts and with the proper posture of humility such a quest demands. The Mystery will not be rushed.

THE NEO AXIAL AGE: FINAL THOUGHTS

In this series of essays, I have offered my thoughts as just one voice among many. I know my ideas are imperfect at best. I don’t pretend to have all the answers, or even all the right questions. My hope is that the ideas I have shared here may spark even better ideas in you. After all, whatever this is that is happening to us, we are in it together, and must find our way together through it. If something I have written in these eight installments has given you an actionable idea that is better than any I have shared, then I have done my work well.

A leader I once worked with was fond of this saying: “Living things grow. Growing things change.” He said it in reference to his growing organization, and the often uncomfortable changes that growth evoked, but the principle applies to any kind of life — from a single-celled paramecium to the collective human species sprawling across the Earth.

Living things grow. Growing things change.

As living things grow, they must of necessity leave behind what they used to be. This is the very definition of loss. We cannot become something more or different and remain what we have been at the same time. Loss, and by extension, grief, is an intrinsic aspect of all growth, even very good and beneficial growth. Ask any parent and they’ll tell you: how they love watching their children grow up, and yet grieve each new milestone at the very same time.

Living things that don’t grow, die. They become stagnant. They dry up. They start consuming themselves, until there’s nothing left but a husk. Eventually, they collapse into themselves, and fall to dust. Then the world moves on, creating new life out of their remains.

Humanity is a living thing. If we are to keep living, we must grow. If we are to grow, we must change. Without growth and change, we will stagnate and die.

Right now, as a species, it seems to me we are trying to decide whether we want to grow or die: whether we want to curl back into ourselves, into the illusory safety of the known ways of our past, even though somewhere inside our collective intelligence, we know that to choose this means we will die; or, to brave the wilderness of the Great Unknown that has not only come pounding its terrifying fists on the front door of our reality, but has effectively ripped the door clean off its frame, and to trust that somewhere in that Great Unknown there will be a way forward that will not only allow us to survive together, but to thrive, to grow, and to become something better than we have been up to now.

We are at an inflection point in our journey as a species. We are peering over the precipice toward an uncertain future, saddled with the choice between Faith and Fear. It is the same old battle our kind has always faced in our short sojourn through time, writ large once again across our collective consciousness.

Can we find the courage to forge a new way forward together, or will we collapse under the weight of a past that can no longer carry us?

I am convinced that we can. History teaches us that we don’t even need the masses to change. As the great cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead once wrote:

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.”

All it takes is a committed minority. We just need a few shining lights to stand up and guide us through the dark.

What if you were one of them?

(Note: This is the 8th installment in a series of essays. You can find all the entries by following these links: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, and Part 8.)

I realize I have cited this teaching from O’Donohue once before in this series, but believe it is worth mentioning again, given the focus of this particular essay.

Despite my best efforts, I was unable to locate the original creator of this image so I could cite the source. If you happen to know it, or know how to find it, I would appreciate you letting me know. I want to give proper attribution for the image. Thanks!

This series has given me a lot to think about. It confirms intuitions that's I've had for a long time. Many secular people are saying the same thing - "It feels like everything has changed." Thank you for the work you put into this series, I'll be thinking about it for a while!

Michael, this series has been awesome! Your insights are so timely, and I really appreciate the depth and care you’ve put into each essay. Grateful for your work and excited to see where these ideas take us next.