“It is a joy to be allowed to be the servant of the work. And it is a humbling and exciting thing to know my work knows more than I do.” — Madeleine L’Engle

It’s a strange thing writing a novel. You can never shake the sense that the story isn’t coming from you. It’s coming through you, from Somewhere Else. It’s like you’ve been selected as the emissary for a work that carries the scent of the Divine. You’ve been entrusted with it for God only knows why. Maybe you won some kind of cosmic lottery, or there’s some Divine plan at work that’s far beyond your reckoning. Or maybe you were the only schmuck who happened to be available at the time the story needed telling. The only thing you really know is that you’ve been handed something precious, and you’d best not muck it up.

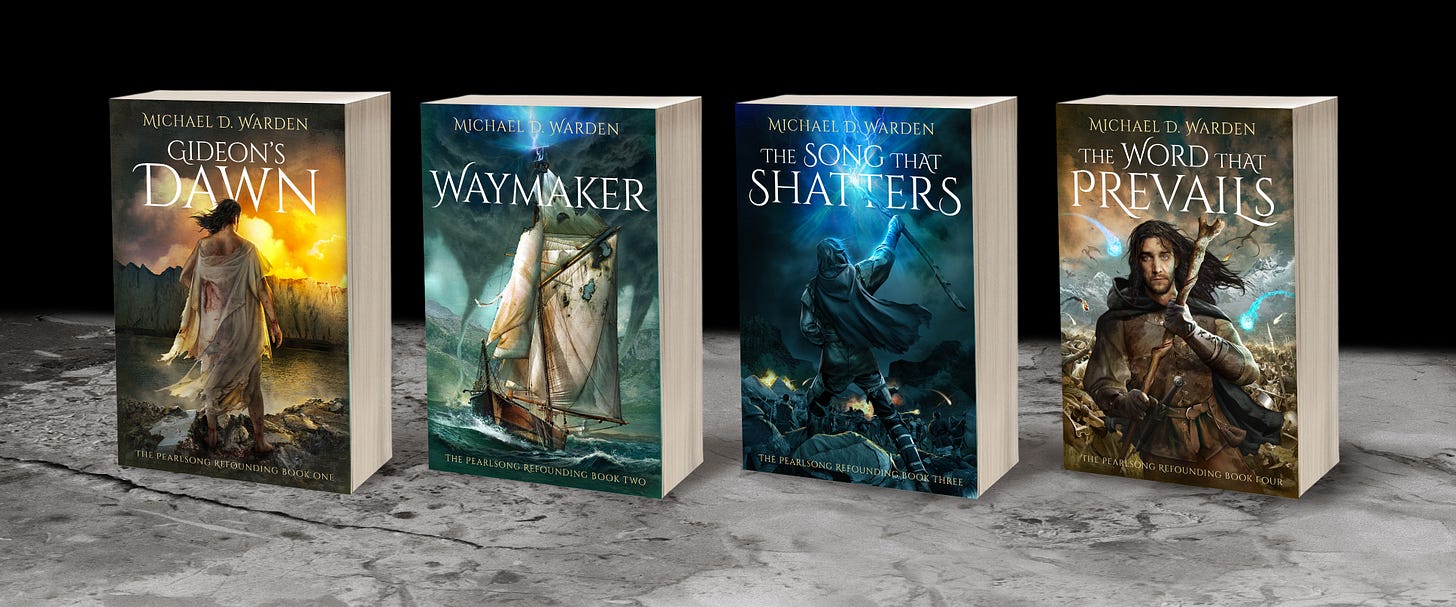

The whole time I was writing The Pearlsong Refounding tetralogy, I had the sense that the story was bigger than I was, that it was older somehow, wiser and more fully formed, that it always knew better than I did what it wanted to be—what it already was, really, in that other realm from which it emerged—and the best thing I could do was listen, and write, and do my best to keep my meager wordcraft from getting in the way.

It was just the same with the characters, too. They each came to me in their turn as any person would, walking into my field of view as a stranger appearing from another room. I saw them, but did not know them. It took time to find out who they were, some much more time than others, and even longer to discover why they were in the story, and what they had come to teach me. For all of them have become my teachers (again, how could that be unless the work was somehow older and farther along than I am?), and I have been humbled again and again by their instruction, in spite of my ofttimes stubborn resistance to their lessons.

Of these, perhaps the most shocking and life-altering has been the realization—the revelation, more like—that the “work” of creating these novels is in essence precisely the same as the work of creating my life…my real life, I mean, that true, deep, burning-with-aliveness life that keeps demanding its time in the sun. The books birthed in me this sharp-edged awareness, cast like a new sun over my days, that the deeper story of my life is somehow older and wiser than I am; that it, like the story of the novels, already knows what it is and wants to be, and that it is doing all it can to get me to stop striving so damn hard to “make something” of my life as the world would have me make it; and, instead, to shut up and listen to what it is trying to tell me.

I don’t mean to take a personality test, or sign up for a course on self discovery, or anything like that (though I value such instruments and have benefited greatly from them). I mean to get still and quiet for a very long time, and to really listen to my life. John O’Donohue taught that all of us need to take extended time to listen to our own souls with great care and patience, as you would listen to a close friend you dearly love.

says something quite similar, writing in his powerful book Let Your Life Speak:“I must listen to my life and try to understand what it is truly about—quite apart from what I would like it to be about—or my life will never represent anything real in the world, no matter how earnest my intentions.”

I’ve always had this feeling that my life was waiting for me to stop futzing about and get on with the real work of living. For me, that “real work” has always been an enigma wrapped in a mystery, ever befuddling to my task-obsessed, status-conscious mind. But in the wake of its frequent flights above the mundanity of my days, I have never failed to catch in its passing the unmistakable scent of freedom. That aroma has haunted me for longer than I can remember. It has been relentless, even merciless in its way, coaxing and seducing my weary, worn-down bones to let go and take flight.

But take flight where? How? When? To what end? My poor strategic mind has gone mad with not knowing.

My mind wants a plan, you see. It’s addicted to plans. It wants assurances. Guarantees. It wants to know where it’s all headed before it says yes. My fear demands it.

But that’s not the way a real life works.

That’s not the way writing works either.

Early on in writing the novels, I learned I was not really the one in charge. The characters had minds of their own, as it turned out. They went left when I wanted them to go right. They refused to do things I had clearly spelled out for them in the plot for very good plot reasons. Even the environments where the action took place did not always behave as I wished. Creatures ran away instead of attacking. The weather did not cooperate. It was maddening to my ego, and I legitimately wondered if I actually was going a bit mad. Was I not the author of this story? Was I not the one in charge of the narrative?

That answer, I eventually had to admit to myself, was no. At least, not in the way I believed at first. At first, I thought I was dictating a story of my own creation. But that’s not the way storycraft works. The truth is, I was co-creating a story with unseen forces I did not understand. My voice did matter, immensely, in the process, and it is fair to call the whole endeavor “my work.” But mine was not the only voice at play. I was a “servant of the Muse,” as they called it in the old days. The story, older and wiser than I could see, came to me with its own intentions, and I could either humble myself and surrender to the collaboration it wanted from me, or drop the whole enterprise and let the Muse move on to someone more willing.

So, I surrendered. And the books were written. It was only afterward, when the work was done, that I came to the revelation that has fundamentally altered the way I live:

Everything I learned

about creating my novels

is also true

about creating my life.What if the deepest, truest aspects of the story we’re meant to live come from Somewhere Else? What if our lives are nascent works of art, like a novel or a song, and in the making of our lives each of us is asked to “be a servant of the Muse,” just as I was for the novels? If so, then to make the art of our lives real in the world, we can’t force our will on it or try to control every aspect of the drama. We have to listen—to really listen—to what our lives are trying to tell us. And only then, once we hear it, to take the heart-pounding risks necessary to write the real story we hear, to embody that story, and to tell it as beautifully and as honestly and as simply as we can.

I now believe that living my real life, the one I’m made to live, is above all other things, about surrender. It’s about letting go. Forsaking fear, and choosing to trust in the Great “I Don’t Know” in ways I’ve never trusted before.

I’ve heard plenty of sermons about the virtues of prudence and safety and the “wisdom” of building fortresses to seal yourself in and keep danger at bay. But if I have learned anything in my six decades of following that path, it is that living that way might or might not keep you physically safe, but it will most definitely choke every last drop of real life from your soul. It is a prison of fear disguised as good judgment. It cannot lead you to anything resembling authentic life or real joy.

Sadly, once you invite fear to be your defender and guide through this world, as I have done, it will not go quietly when at last you decide you don’t want it running things any longer. It will not simply leave when you hand it its papers. It will fight like hell to keep you in its grip.

I’m not making an excuse here. I’m just saying the battle is real.

The call to one’s real life, though, is equally relentless, and, thankfully, a fair bit stronger, for those who have ears to hear it.

“Place me like a seal over your heart,

like a seal on your arm;

for love is as strong as death,

its jealousy unyielding as the grave.

It burns like blazing fire,

like a mighty flame.”

— Song of Songs 8:6

“There is no fear in love. But perfect love drives out fear, because fear has to do with punishment. The one who fears is not made perfect in love.”

—1 John 4:18

I suppose the central question of my life these days is “Do I have ears to hear?” My real life is calling to me from that mysterious Somewhere Else, and somedays I find I have the grace to run full speed toward it. Occasionally, even, I fly. But many days I find my body sprawled in the dust, crawling my way forward, terrified with every shuffle and scrape of my knees against the raw earth. On those days, I claw and grapple my way the best I can to what is real, and true, and authentically mine.

But I hear the call. I am listening. And I am moving, even if sometimes it is only at a crawl.

I think, maybe, that’s all that matters.

P.S. For those curious, the novels are currently in production, and will be available soon. As that day draws near, you can bet you’ll hear about it. I’ll be shouting it from the rooftops. :)

Thank you for this writing.

For several years now, I Kings 19 has called to me, over and over again.. “Kavina, what are you doing here?” And more times than I appreciate, the mind shouts “I do not know, but I want to.” And so I chased the wind, time and time again.

And yet, the call is whispering again, “Kavina, what are you doing here?”

You are right that the fear does not go quietly. I pray I can be content with at least listening and crawling. Honestly it’s just so hard.